Shopping Cart

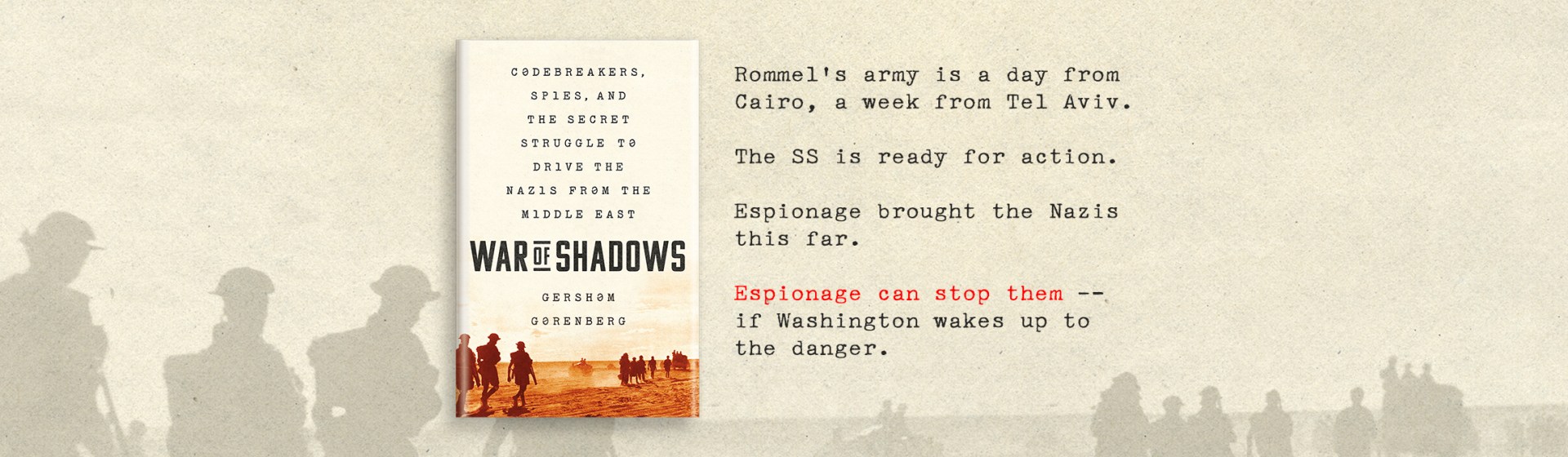

War of Shadows

Codebreakers, Spies, and the Secret Struggle to Drive the Nazis from the Middle East

Description

As World War II raged in North Africa, General Erwin Rommel was guided by an uncanny sense of his enemies’ plans and weaknesses. In the summer of 1942, he led his Axis army swiftly and terrifyingly toward Alexandria, with the goal of overrunning the entire Middle East. Each step was informed by detailed updates on British positions. The Nazis, somehow, had a source for the Allies’ greatest secrets.

Yet the Axis powers were not the only ones with intelligence. Brilliant Allied cryptographers worked relentlessly at Bletchley Park, breaking down the extraordinarily complex Nazi code Enigma. From decoded German messages, they discovered that the enemy had a wealth of inside information. On the brink of disaster, a fevered and high-stakes search for the source began.

War of Shadows is the cinematic story of the race for information in the North African theater of World War II, set against intrigues that spanned the Middle East. Years in the making, this book is a feat of historical research and storytelling, and a rethinking of the popular narrative of the war. It portrays the conflict not as an inevitable clash of heroes and villains but a spiraling series of failures, accidents, and desperate triumphs that decided the fate of the Middle East and quite possibly the outcome of the war.

What's Inside

We were eavesdroppers, strangers reading stolen scraps of other people’s correspondence.

—The History of Hut 3 (Top Secret Ultra)

God delivers his will as visible in events, an obscure text written in a mysterious tongue. People toss off instant translations of it, hasty translations that are incorrect, full of faults, omissions and misreadings. Very few minds understand the divine tongue. The wisest, the calmest, the deepest, set about slowly deciphering it, and when they finally turn up with their text, the job has been done; there are already twenty translations in the marketplace. From each translation a party is born, and from each misreading a faction; and each party believes it has the only true text, and each faction believes it holds the light.

—VICTOR HUGO, Les Misérables

NAMES OF PLACES and countries are given in the form common at the time of the events. There are many ways to spell Arabic and Hebrew names in English. The spellings here are ones commonly used at the time or, when available, that individuals used when writing in English.

Not only do British and American spellings vary, but in some cases more than one form was used. For instance, both cipher and cypherappear in direct quotations from British documents.

THE MEDITERRANEAN THEATRE

OVER LUNCH IN Jerusalem, my friend Daniel Avitzour mentioned that his father had been a British officer in Palestine during World War II, and that the British army offered to evacuate his mother to South Africa. Or perhaps it was a demand that she leave the country, since Palestine was likely to soon be a battlefield. In either case, she refused.

That conversation set me on a journey that lasted years—to Rome, to Cairo and the sands of El Alamein, to London and the once-secret huts of Bletchley Park, to archives in places from Tel Aviv to Palo Alto, to the homes of the children and grandchildren of people whose names have been forgotten though they changed the direction of history. It was also a journey of the mind, of countless long days and nights spent fitting together the recently declassified or long-lost or long-secret documents of one country with espionage reports of another, of following one lead to another to find someone who still remembered the face and voice of a mysterious woman who’d once tracked spies—obsessed, I admit, amazed as I watched established facts unravel and new ones take their place. In the end, I was able to create a distinctly new portrait of one of the great turning points of the last century.

This is a true story. It is drawn primarily from the documents of the time, official and private. Some papers had remained classified for as long as seven decades. I have also consulted, carefully, even warily, the later memories of people who played a part, and have benefited from the research of many other historians. If a conversation appears here, it was recorded by someone who took part; if the temperature on a certain morning appears, it was written down by someone who suffered the heat or cold. To avoid breaking the flow of the story, the attributions and some technical information about codebreaking appear in the notes.

One human lifetime ago, the battle for the Middle East was one of the critical fronts of World War II. Much of what determined the outcome of that battle, and therefore of the war as a whole, remained secret. Quickly shaped legends turned into accepted memory. Today even that misleading memory is fading. Yet what happened then shaped the Middle East, and continues to shape it today.

Stories have lessons. But lessons are best told after the story, not before. Thus have I done.

Daniel, to my great sorrow, is no longer here to read this. Still I thank him for sending me on the journey.

CURTAIN RISING: LAST TRAIN FROM CAIRO

Early Summer, 1942. Cairo.

THE WORLD AS everyone knew it was coming to an end.

In the vast desert west of the Nile, the Eighth Army of the British Empire was in full flight from the German and Italian forces commanded by Field Marshal Erwin Rommel.

SMOKE ROSE FROM the grand British embassy facing the Nile. Smoke rose a few hundred yards down the river from the mansions of Garden City that war had transformed into British General Headquarters Middle East. In the Cairo heat, privates fed bonfires with all the paper that must not fall into enemy hands—cables from London, lists of arms, reports radioed in cipher from the battlefield, maps, and codebooks. The flames were too hot, the updraft too strong, and half-burnt secrets floated out over the city.

Smoke rose from the office of the Special Operations Executive, the secret undisciplined unit that backed partisans throughout the occupied Balkans and now was trying to erase its chaotic records. At Royal Air Force headquarters, too many papers were dumped too quickly down a chute to an incinerator. Some wafted whole over the fence and into the streets, which were packed with dusty trucks pouring in from the desert carrying exhausted soldiers, and with convoys evacuating rear units east to Palestine, and with the cars of wealthy Alexandrians who’d fled to Cairo and the cars of rich Cairenes trying to get through the traffic to flee south or east. Everyone honked, as if the horn were the gas pedal.1

The pillars of smoke stood over the city and gave no guidance to the exodus.

ON THE MORNING of her nineteenth birthday, June Watkins emerged from the Metropole Hotel in downtown Cairo. That’s where the Royal Air Force had tucked its cipher office. Around a long table, officers of the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force worked as fast as they possibly could, turning words into opaque groups of numbers to be sent out in Morse code by radio, or translating equally opaque numbers from field units back into words. In the summer, the room was too hot, even at night, even if you were wearing a thin cotton tropical uniform. Watkins’s commander was “quite old,” meaning at least twenty-seven, and had once deciphered a list of pilots who’d been shot down. It was from the squadron in which the commander’s boyfriend served. His name was on it. The commander passed on the list and said nothing. No one ever gets a medal for that kind of heroism.2

Watkins’s father had wired her £20 for her birthday, a fortune, two months’ salary for a woman officer, and she headed for the bank to see if it had arrived. The lines outside stretched for blocks.3 When she got inside the grand marble-walled lobby, she found it packed with Egyptian businessmen trying to withdraw their money.

By sheer chance, a large South African captain, an old friend, recognized her and helped her shove through the bedlam to the counter. The man in front of her ranted steadily in French through the grating at the clerk who was counting out his money. The banks had run short of cash and were handing out worn banknotes while waiting for the government map department to improvise printing an emergency supply.4 The man grabbed his notes, accidentally tore some, and started weeping as he cursed the clerk. Calmly, the clerk got Watkins her money. The captain plowed back out through the crowd for her.

Outside they met another South African officer. “What are you still doing here?” he demanded. Women soldiers were supposed to be gone. Five hundred South African women had already been evacuated up the Nile to Aswan.5 Watkins was billeted in the Cairo YWCA hostel, a palace with marble floors outfitted with iron camp beds for soldiers—but nearly all the women were gone.

Her team would remain till headquarters pulled out, she said. “And I want to stay,” she added. “I can look after myself.” She tapped the bulge of a pistol under her shirt. She did not tell him that the same week, on the roof of the Metropole, the women of the cipher room had received a lesson in using pistols.

Among other things, they learned how to shoot themselves. Women who knew the ciphers were not to fall into enemy hands.

Her friend the South African captain took her to Groppi’s café, a favorite among British officers. They wanted to drink iced coffee in the garden but were told it was closed, so they sat inside. From the window of the ladies’ room, Watkins looked into the garden. The restaurant staff was out there, painting welcome signs in German for Rommel’s officers.

At stores that sold suitcases, as at the banks, crowds of people pushed to get in.6

OUTSIDE CAIRO’S TRAIN station stood the granite colossus called Egypt’s Awakening—a sleek, angular sphinx rising on his outstretched forelegs, facing east toward the dawn, next to the taller figure of a woman lifting a veil from her face. The woman was inspired by Egyptian feminist Huda Shaarawi, who in 1923 had returned from a women’s conference and demonstratively removed her veil in the train station.7 The station itself, studded with arches and intricate carved arabesques, was modeled on the mosques of Cairo’s medieval Mamluk sultans.8 Together, the sculpture and the railway hall formed a temple to Egypt, its future, its incomplete independence.

Inside, the god of chaos ruled. Trains from Alexandria disgorged anxious mothers and fathers dragging suitcases and children. They had to shove their way out through the wave of soldiers and families from Cairo trying to board trains headed south or east. South lay Aswan in Upper Egypt and, much further, Khartoum in Sudan. East lay the port of Suez, for the fortunate who had managed to book passage to Eritrea, Kenya, or South Africa.9 Or you could gamble on safety in Ismalia, on the Canal. Even if the Eighth Army lost the Nile, surely it would hold the Canal.

If that seemed a poor wager, there was the all-night express to Jerusalem.

For Palestine, you needed the right papers. Halfway across the Sinai, police boarded the train to check everyone.10 The British consulate, war correspondent Alan Moorehead found, was “besieged with people seeking visas to Palestine.”

Praise

—Publishers Weekly