Shopping Cart

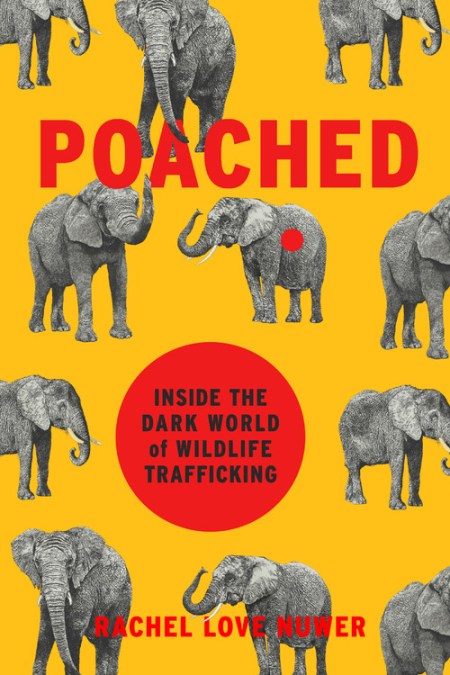

Poached

Inside the Dark World of Wildlife Trafficking

Description

Journalist Rachel Nuwer plunges the reader into the underground of global wildlife trafficking, a topic she has been investigating for nearly a decade. Our insatiable demand for animals — for jewelry, pets, medicine, meat, trophies, and fur — is driving a worldwide poaching epidemic, threatening the continued existence of countless species. Illegal wildlife trade now ranks among the largest contraband industries in the world, yet compared to drug, arms, or human trafficking, the wildlife crisis has received scant attention and support, leaving it up to passionate individuals fighting on the ground to try to ensure that elephants, tigers, rhinos, and more are still around for future generations.

As Reefer Madness (Schlosser) took us into the drug market, or Susan Orlean descended into the swampy obsessions of TheOrchid Thief, Nuwer–an award-winning science journalist with a background in ecology–takes readers on a narrative journey to the front lines of the trade: to killing fields in Africa, traditional medicine black markets in China, and wild meat restaurants in Vietnam. Through exhaustive first-hand reporting that took her to ten countries, Nuwer explores the forces currently driving demand for animals and their parts; the toll that demand is extracting on species across the planet; and the conservationists, rangers, and activists who believe it is not too late to stop the impending extinctions. More than a depressing list of statistics, Poached is the story of the people who believe this is a battle that can be won, that our animals are not beyond salvation.

What's Inside

The hostess at the posh Ho Chi Minh City restaurant sat us at a front street-facing table and handed over massive, leather-bound menus. Opening mine, I wanted to quickly paw through to see what kind of wildlife horrors might be advertised, but I forced myself to slowly survey the options like a normal customer. I smiled vacantly, glancing over all the usual suspects of chicken, pork, duck and beef, along with various noodles and rice dishes. But then, with the turn of a page, the motherload arrived.

In the very back, complete with photographs, were several pages advertising a menagerie of wild animals. Fried bats were pictured next to the bony legs and rat-like tail of a roasted civet on a platter adorned with greens; on the next page, a boiled pangolin lay splayed out on a plate in a morbid belly flop. Some photos, rather than depicting prepared dishes, took the even less subtle approach of displaying the actual animal in question: a porcupine, two grinning bears, a bright green lizard, a turtle and more. Thảo translated a few of the offerings, including pangolin stewed with Chinese herbs; snake meat sausage; fried tortoise viscera; and bear paw cooked with ginger (24 hours’ notice required).

I was dumbfounded. I hadn’t known what to expect, but an illustrated menu of illegal products handed out to anyone who walks through the door was definitely not it. I quickly snapped a few photos of each menu page, even daring to whip out my conspicuous SLR. No one seemed to notice or care. The food soon arrived, and conversation turned to other things. At one point, Thảo and I took a break to visit the ladies’ room, peeping into the kitchen as we made our way through the restaurant. But everything appeared to be completely normal: no animal cages, no protected species on the cutting board, no pile of severed bear parts or pangolin scales. The night, it seemed, would end without further incident.

My courage was steadily growing, reinforced by the beer and the mundane uneventfulness of the visit. I decided to try my luck with an interview, and Thảo agreed that things seemed safe enough. By this time, the place had begun to fill up with couples, groups of men and even families with toddlers, so I figured we were probably safe from physical attack at least, given all the potential eye witnesses. Minutes after Thảo asked to speak with the manager, a soft-faced young man with an eager smile appeared at our table. His name tag, pinned next to a yellow smiley face button, read Quóc Trung.

Through Thảo, I told Mr. Quóc that I was an American journalist researching exotic meat in Vietnam. “Oh yes, that is our specialty,” he said, nodding. He either did not notice or did not mention that it was odd that our table had not sampled a single piece of said specialty, despite that being the purpose of our visit. I had jotted down a list of questions to ask, but Mr. Quóc needed little prompting. Thảo could hardly keep up with the translation.

“Exotic meat is extremely popular,” he began. “Civets and pangolins especially. Tortoises and snakes sell well, too. I think civet served with sticky rice is the most delicious.”

When asked about the exorbitant price tag for pangolins, he explained that it stems from the fact that they cannot be raised in captivity. “Everyone wants them,” he said. “But only high-class and special guests get to enjoy this animal.”

“But why do people want pangolin—what makes it worth paying so much?” I prodded.

“People are willing to pay, not only because the pangolin’s meat is tasty, but also because the pangolin’s scales treat a lot of sicknesses,” he confidently informed me. “The scales are good for the body. They can treat all sorts of things, like back or joint pains. Or if a woman is having trouble lactating, she can take them to help her produce milk.”

Judging by his earnest tone, it did not seem like he was just making this stuff up to try to push his pangolin products. He believed it—and customers apparently did, too. Those who order a pangolin almost always want to keep their animal’s scales, he told us. The fee patrons pay for their pangolin includes removing, drying and packaging the scales up into a doggie bag to take home with them.

Dũng piped up with his own question, finally understanding this game. “So does the government allow this?”

“No,” Mr. Quóc smiled slyly. “But we have our sources. We get no problems from the authorities because we have good connections with the police. Although everyone knows it’s banned, we can still advertise it and put the pictures in the menu—we don’t have to worry about anything. Anyway, the demand is so high for these things, we have to supply them.”

Mr. Quóc didn’t know the origin of the animals that found their way to his restaurant, but added that once the animals reach his kitchen, they have already changed hands many times.

“Oh, look, that table has ordered a cobra!” Mr. Quóc interrupted himself, gesturing to a five-top composed of two white men, two Vietnamese women and an older Vietnamese man. Overweight, middle-aged and wearing ill-fitting polo shirts and glasses, the two foreigners looked like they belonged in a sad suburban office park, not a posh restaurant catering to a wealthy Vietnamese clientele. Speaking French to each other, they switched to Vietnamese when addressing their dates, who were trim, well-dressed and also appeared middle-aged.

Two servers clad in red uniforms with clown-like yellow buttons had just come out of the back, pushing a plastic trolley with a silver tray and white ceramic bowl on top of it. One carried a large yellow mesh bag. Inside, it appeared that something was moving. “You can take photos if you’d like,” Mr. Quóc offered helpfully.

Unlike me, the Frenchmen were not seeking permission. Grinning and rising from their chairs, one of them whipped out an iPhone, the other an iPad. The women remained seated, but their dates crowded close to the cart. I jumped to my feet, too, dreading what I suspected was about to happen, yet knowing this was what I had come here to see. The servers untied the bag, reached in and withdrew a writhing black cobra, its mouth tightly bound with a bit of green twine. The snake had to be at least five feet long. It thrashed and twisted, fighting for its life. Almost certainly plucked from a rice paddy or forest days or weeks before, I imagined the deadly predator was for the first time experiencing an uncomfortable new sensation: fear.

With their ear studs, tattoos and swooped bangs, outside of work the young men holding the snake could very well be Vietnamese hipsters. But here, they were animal-killing professionals. They went about their duties with a practiced ease, as though they were preparing nothing more complicated than a venti latte. Swoop boy, the shorter of the two, grasped the snake’s throat in his left hand, its tail in his right, and extended his arms, which were not quite long enough to hold the animal taut. Tattoo boy then felt along the snake’s stomach with his thumb, forming a painful-looking indentation in its body as he worked his way up toward its head. At last, he found what he was looking for. Grabbing a pair of black-handled scissors, he inserted the tip into the snake’s belly, and then wiggled it around until he was able to slip one of the blades under the skin. Then, he began to cut.

The snake’s pupils dilated and its purple tongue slipped out of its bound mouth as though it were panting. If snakes could scream, this one certainly would be. Vibrant red blood began to seep, and then pour, from the incision, now about five inches long. Meanwhile, the French men who had ordered this execution were scurrying to and fro, trying to find the best angle to film the spectacle.

The show, it turned out, was just getting started. Tattoo boy inserted three of his bare fingers into the moist slit, feeling around thoughtfully and then pulling. Grasped delicately between his now blood-coated thumb and index finger was the cobra’s beating heart. With one final snip, it was all over. Into a small dish went the heart, out went the cobra’s life.

“Are you going to eat that?” I asked incredulously, turning to one of the Frenchman. Without breaking his gaze on the snake, he nodded sternly, his brows furrowed in concentration—or perhaps annoyance.

Swoop boy now angled the animal’s body downward while tattoo boy worked the scaly corpse like a tube of toothpaste, squeezing the blood into the ceramic bowl. Its pristine whiteness made the shock of red all the more stark. Later, the blood would be mixed with alcohol, to be taken in shots in a show of masculine bravado. Although the snake’s eyes were glassy, its body, as if still unable to accept the finality of its fate, continued to twist and spasm.

The shrimp paste and fried spicy tofu no longer seemed so settled in my stomach. The servers were still working the snake over, however, so I forced myself to continue looking, snapping photos every few seconds. Out came the animal’s viscera, along with globs of bright yellowish fat. Finally, swoop boy took the snake’s head, and with a couple of determined snips, tattoo boy decapitated it. I turned away, sensing the show was over.

Floating back to our table, I lowered my numb body into my chair, staring at my friends in blank shock. Just then, Mr. Quóc reemerged from the kitchen, bearing yet another yellow mesh bag. Oh God—more?? I really did not feel up to seeing another animal being tortured to death.

This bag contained a civet. It was about the size of a Yorkie but with a fur patterns reminiscent of a raccoon. Its snouted face was lowered in defeat; any fight it once had, it seemed, had long since been extinguished. It reached up, placing its small, cat-like paws against the sides of the bag, as if trying to brace itself for what was to come. It hardly moved from that position even as Mr. Quóc wildly spun the bag and tossed—nearly slammed—it carelessly to the ground.

My chest clinched in bitter, helpless frustration. I had experienced this sensation before. Memories flooded back: a day on the playground when a group of tyrannical third grade boys began stomping on baby toads that had just emerged from spring puddles; a kitten that was brought into the veterinary clinic where I worked, caked in blood and comatose after the owner’s boyfriend had kicked it across the room; a group of teenage visitors at a zoo in Vietnam who used a hose to water cannon caged animals while the staff placidly looked on.

Mr. Quóc was saying something, but by this point--if Thảo was translating at all--it no longer registered. “I think we should go now,” I said, abruptly rising from the table and now feeling less the urge to vomit as to cry. Ty, who looked like a deer in the headlights, nodded emphatically.

Fetching the motorbikes, we reconvened outside in stunned silence. Even Dũng seemed to be at a loss for words. Finally, Ty cleared his throat. “Obviously, that was absolutely horrifying… But wow! That manager really just sang for you like a canary. Not that a canary would sing here for very long…”

I laughed, grateful for the icebreaker.

“My uncle trusts this kind of thinking, that you can eat exotic meat and blood and recover from illnesses,” Thảo said. “Many old Vietnamese think this way. But those poor animals… Why can’t they just eat duck or chicken? They’re perfectly delicious and fine!”

“Or vegetables,” Ty added dryly. He admitted that he had averted his gaze throughout the entire snake spectacle. “I just couldn’t do it,” he said, looking down. “I couldn’t watch that.” In a way, I envied him.

As we pulled away, I could hear the women clapping and cheering shrilly as the Frenchmen took their first shots of the cobra’s still-warm blood.